#363 – October 26, 2018

Over the last 30 years I have been into wine (the last 12 of which I have been penning this newsletter), the world of kosher wine has undergone seismic changes with many trends coming and going, the most prominent of which has been the explosive growth in those drinking and enjoying kosher wines. Responsive to this growth has been the continuously expanding array of available quality kosher wines from around the globe, which can be tracked through my personal prism of the shifting Holy Grail. While the ultimate Holy Grails of a kosher First Growth red Bordeaux and Chateau d’Yquem remain elusive (while being closer than ever before), many others have been achieved over the last decade or so, each making way for the next as the milestone has reached. Former targets have included top-quality versions of Napa Valley Cabernet Sauvignon (e.g. Covenant, Napa Valley Reserve and Mayacamas – check), first-rate Bordeaux and Sauternes (e.g. Chateaux Léoville Poyferré, Lascombes, Gruaud-Larose, La Tour Blanche, and of course Guiraud – check) and Burgundy (e.g. Château du Clos de Vougeot, Domaine d’Ardhuy Gevrey-Chambertin and others – check), with the most recent unicorn recently succumbing – true German Riesling, the greatest white wine grape of them all and the subject of this week’s newsletter. While Koenig, Alsace’s kosher producer has been making Riesling for decades and another Alsatian producer – Willm had a lovely 2008 make its way to the US, it is only now that the quality and consistency has reached acceptable levels, and the first time German Riesling has been made kosher (as part of the three German winery partnership called Gefen Hashalom).

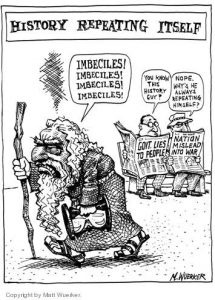

Know Your Past (or else)

Easily one of the world’s most underappreciated grapes, for the last century Riesling has also been one of the most polarizing. However Riesling goes back much further, with one of its first documented mentions being in the mid-1500s, when Riesling was included in the wine inventory of Count John IV of Katzenelnbogen. DNA testing has identified it as a cross between wild vines and Gouais Blanc, one of Western Europe’s oldest grape varieties, and its birthplace is thought to be Germany, somewhere along the ancient Rhine. Especially surprising given the grape’s acknowledged greatness, its etymology is shrouded in mystery, with no clear understanding of the name’s source. One theory is sourced from the old German word Rizan (to split) but no rationale is given.

Easily one of the world’s most underappreciated grapes, for the last century Riesling has also been one of the most polarizing. However Riesling goes back much further, with one of its first documented mentions being in the mid-1500s, when Riesling was included in the wine inventory of Count John IV of Katzenelnbogen. DNA testing has identified it as a cross between wild vines and Gouais Blanc, one of Western Europe’s oldest grape varieties, and its birthplace is thought to be Germany, somewhere along the ancient Rhine. Especially surprising given the grape’s acknowledged greatness, its etymology is shrouded in mystery, with no clear understanding of the name’s source. One theory is sourced from the old German word Rizan (to split) but no rationale is given.

Long loved by Europe’s upper classes, during the late 18th and early 19th century, Riesling’s popularity really took off, as it was revere for its long-term aging ability and other wonderful qualities discussed below. Its soaring popularity only made the fall from grace during the second half of the 20th century which was exacerbated during this period (the 1950s and 1960s) when boatloads of severely mediocre white wines debased the might Riesling name by using it to market their insipid creations (while imitation is the most sincere form of flattery, this is one instance where no publicity would have been better). Riesling’s cache leads its name to be bastardized for other, less popular, versions in the hope some of the glamour will help sell (with Italian Welschriesling giving the proud Germans the most grief). Other names Riesling is actually known as include White Riesling, Rhine Riesling and perhaps most famous – Johannisberg Riesling (names for the famed 200 acre Schloss Johannisberg vineyard, the region’s most famous vineyard, whose acclaim dates back to the 15th century).

Adding insult to injury were the subsequent years, when Robert Parker led the wine world on a merry chase after, heft, oak-aging and ripe flavors, all things Riesling shies away from; making it even less than popular among the fervently score-chasing wine enthusiasts. Further distancing folks from the remarkable Riesling was the tendency of many German (mostly mass) producers to turn out overly sweet Riesling wines that lacked sufficient acidity and extraction to maintain the breathtaking elegance and crisp refreshingness for which the varietal should be known. However, as the wine world slowly shifted back to subtle, elegance and food-friendliness as valued wine characteristics, Riesling started to regain its position of honor (as levels of RS decreased), especially among the more sophisticated wine lovers, with many young up-and-coming helping lead the charge as they incorporated Riesling in to the wine lists at their top-ranked eateries (and continue to do so).

The Great White Hope

With natural high acidity, relatively low alcohol and abundant fruity and mineral notes in perfect balance, Riesling produces some of the world’s greatest white wines, many of which have an astounding ability to age for decades (a quality discovered as the wine rapidly curried favor with Germany’s noble and aristocratic classes who stockpiled it and found it lasting far longer than expected) regardless of their level of residual sugar or AbV. However, it is the grape’s terroir-reflective capabilities that are its greatest asset, contributing to its far-ranging global production and startlingly wide range of styles and dryness levels (one of the kosher Riesling producers – St. Urbans-Hof, produces nearly a dozen Rieslings annually, all in distinct styles). Similar to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, Riesling is somewhat of a chameleon, taking on many of the characteristics of the soil and other terroir attributes of its given home. Where is diverges from its peer varietals is Riesling’s amazing ability to retain its defining characteristics regardless of its origin or the winemaking style utilized. Two additional areas in which Riesling stands along from its fellow chameleons is with respect to oak-aging, as Riesling almost never sees any oak (other than in rare occasions where it is gently aged in larger neutral barrels to add a bit of heft) and blending. With a racy personality, high acidity and such a lovely array of aromas, you will almost never find Riesling blended with any other grape varietals. Further distancing itself from Chardonnay, Riesling rarely undergoes malolactic fermentation which helps retain its trademark crisp acidity.

With natural high acidity, relatively low alcohol and abundant fruity and mineral notes in perfect balance, Riesling produces some of the world’s greatest white wines, many of which have an astounding ability to age for decades (a quality discovered as the wine rapidly curried favor with Germany’s noble and aristocratic classes who stockpiled it and found it lasting far longer than expected) regardless of their level of residual sugar or AbV. However, it is the grape’s terroir-reflective capabilities that are its greatest asset, contributing to its far-ranging global production and startlingly wide range of styles and dryness levels (one of the kosher Riesling producers – St. Urbans-Hof, produces nearly a dozen Rieslings annually, all in distinct styles). Similar to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir, Riesling is somewhat of a chameleon, taking on many of the characteristics of the soil and other terroir attributes of its given home. Where is diverges from its peer varietals is Riesling’s amazing ability to retain its defining characteristics regardless of its origin or the winemaking style utilized. Two additional areas in which Riesling stands along from its fellow chameleons is with respect to oak-aging, as Riesling almost never sees any oak (other than in rare occasions where it is gently aged in larger neutral barrels to add a bit of heft) and blending. With a racy personality, high acidity and such a lovely array of aromas, you will almost never find Riesling blended with any other grape varietals. Further distancing itself from Chardonnay, Riesling rarely undergoes malolactic fermentation which helps retain its trademark crisp acidity.

With a tendency towards early ripening, historically the grape hasn’t fared well in warmer climates, where, before it can develop sufficient acidity and the full range of tantalizing flavors, it can reach full phenolic ripeness (and beyond), becoming overripe and flabby. While recent years of climate change have allowed many more producers from lesser sites to achieve full maturity (and to abandon the previously common chaptalization required to reduce the tartness in many (lower-classified) Rieslings), Riesling from Mosel remains in a class of its own with a light, crisp and refreshing style that belies its abundance of fruit, layers of complexity and utterly elegant structure. Interestingly, compared to some other summer-intended, quick-ripening varieties growing in Germany’s Mosel region (home to nearly a third of Germany’s Riesling), Riesling has always been considered a late-bloomer who can only reach sufficient ripeness when planted in the highest quality vineyards (which in Germany means, those garnering the most sunlight).

The Many Faces of Riesling

Over the years, much of the Riesling produced tended sweeter, with certain levels of residual sugar viewed as necessary to balance the high acidity; leading to the inaccurate perception that Riesling was a sweet wine. While the high acidity and low alcohol make it great for dessert wines (and it has always been produced across a wide band of residual sugar levels (which remain a huge factor in the wine’s classification system – see below), Riesling’s characteristics make it one of the few grapes that can produce quality wine across the entire spectrum of sweetness, and has always been produced in dry versions with recent years seeing a huge upswing in the percentage of Rieslings fermented until they are bone dry (including the lovely version from Hagafen and the Kishor referenced below). The shift to dry has been so extreme that the majority of German Riesling produced these days is classified as dry (Trocken) or slightly off-dry (feinherb), leaving many traditionalists to lament the diminishing sweeter categories (especially Kabinett (sweet) and Spätlese (late-harvest) whose perception of sweetness was beautifully tempered by high-acidity and harmonious balance( see below for more on German wine classification). However, producers in the prime-growing Mosel appellations of Saar and Ruwer have held the line and continue to produce the fruity Rieslings of yesteryear with sufficient levels of residual sugar to please the neo-cons while yielding elegant and racy wines with gobs of balancing acidity (coincidentally or not, the Saar appellation is the source of the current crop of German Rieslings listed below).

Over the years, much of the Riesling produced tended sweeter, with certain levels of residual sugar viewed as necessary to balance the high acidity; leading to the inaccurate perception that Riesling was a sweet wine. While the high acidity and low alcohol make it great for dessert wines (and it has always been produced across a wide band of residual sugar levels (which remain a huge factor in the wine’s classification system – see below), Riesling’s characteristics make it one of the few grapes that can produce quality wine across the entire spectrum of sweetness, and has always been produced in dry versions with recent years seeing a huge upswing in the percentage of Rieslings fermented until they are bone dry (including the lovely version from Hagafen and the Kishor referenced below). The shift to dry has been so extreme that the majority of German Riesling produced these days is classified as dry (Trocken) or slightly off-dry (feinherb), leaving many traditionalists to lament the diminishing sweeter categories (especially Kabinett (sweet) and Spätlese (late-harvest) whose perception of sweetness was beautifully tempered by high-acidity and harmonious balance( see below for more on German wine classification). However, producers in the prime-growing Mosel appellations of Saar and Ruwer have held the line and continue to produce the fruity Rieslings of yesteryear with sufficient levels of residual sugar to please the neo-cons while yielding elegant and racy wines with gobs of balancing acidity (coincidentally or not, the Saar appellation is the source of the current crop of German Rieslings listed below).

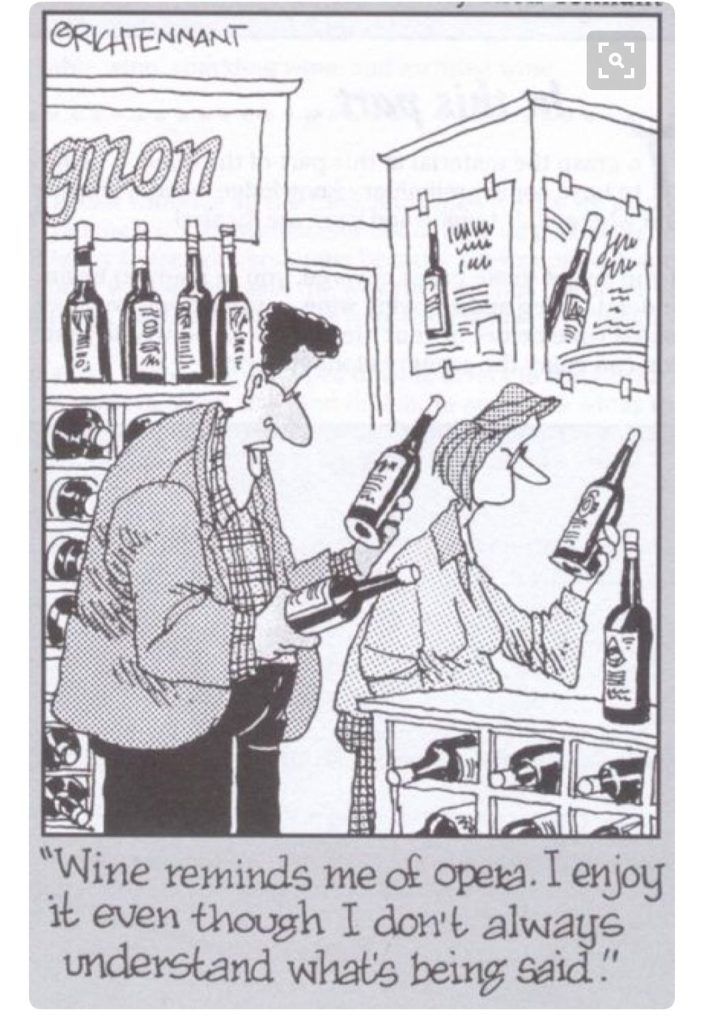

Riesling’s wide-array of flavors, which can include apples and pears, peaches, apricots and other tropical fruits, grapefruit and citrus zest, along with jasmine, floral and honeyed notes and plenty of slate minerals depending on its source, are typified by a sharpness to them which, especially when accompanied by the wine’s bracing acidity, can seem overly astringent and off-putting at first, especially to novice drinkers or those less experienced with Riesling’s unique profile. Combined with Riesling’s naturally high-acidity, the wine’s nose and palate can seem exceptionally sharp. However, it is Riesling’s most defining aroma which as the largest impact – petrol. Caused by the compound TDN (colloquially known as 1, 1, 6, -trimethyl-1, 2-dihydronapthalene), the petrol and kerosene notes tend to increase over time as the wine ages (interestingly, cork absorbs TDN very well, so Riesling’s bottled under screwcaps tend to have more pronounced notes of petrol than their cork-stopped peers). Often not present on a wine’s release, the petrol notes appear rather quickly – often within a year or so (with can coincide with their arrival on the kosher market).

While many folks prefer their Riesling’s without the whiff of kerosene, most of the factors which enhance the aroma are the same as those which contribute to a higher quality and longer-lasting wine (including high sun exposure, lower yields, high acidity and water-stressed vines). Regardless of this fact, Wikipedia notes that the negative view of petrol notes taken by younger drinkers have led many German (primarily mass) producers to significantly reduce such notes, even at the costs of aging ability (another characteristic losing favor among the younger instant gratification generation of drinkers) and the German Wine Institute has omitted petrol as a possible aroma on the German-version of the wine wheel (intended to specifically focus on German wines).

The Primacy of Balance

Maintaining such great balance between high-acidity levels and varying degrees of residual sugar is the primary factor in Riesling topping the food-friendly charts, enhanced by the lack of oak aging and lover alcohol levels with its elegantly voluptuous nose and array of flavors merely providing the cherry on top. A level of residual sugar in some Rieslings further enhances its ability to compliment many tough-to-pair foods, chief among them the spicy notes that dominate many Asian cuisines.

Maintaining such great balance between high-acidity levels and varying degrees of residual sugar is the primary factor in Riesling topping the food-friendly charts, enhanced by the lack of oak aging and lover alcohol levels with its elegantly voluptuous nose and array of flavors merely providing the cherry on top. A level of residual sugar in some Rieslings further enhances its ability to compliment many tough-to-pair foods, chief among them the spicy notes that dominate many Asian cuisines.

As noted above, one of Riesling’s greatest attributes is the ability to age for decades. Many of the higher-quality Rieslings are so austere and acidic on release that they can turn off less-sophisticated drinkers (similar to Bordeaux but for their presumption of prestige which rescues them from having their tight tannins and barnyard funk turning people away). Riesling’s high acidity and relatively low-alcohol make it a prime candidate for dessert wines and they represent the most expensive versions of Riesling produced. Adding abundant residual to a perfect-storm of aging-ability characteristics can juice Riesling’s long-term viability to shocking levels (Michael Broadbent has a multitude of Riesling tasting notes dating back centuries; although given his reliance on recently-deceased Hardy Rodenstock for many of these wines, their viability can legitimately be called into question). [Despite Riesling’s relatively (to its cousin Sauternes across the border) late discovery of Noble Rot’s benefits (in the late 18th century when permission from the vineyard owner Abbey arrived late, after the grapes had already begun to rot and ended up yielding excellent wine), the grape’s elevated tartaric acid levels make it a far more dependable counter to RS than one finds in Sauternes’ counterpart – Semillon.

Despite the inherent difficulties in producing warm-weather Riesling, certain countries have managed to overcome this difficulty, including Southern Australia. Even Israel has recently managed to produce a small number of quality Riesling wines (although very different in style than the Nik Wies and Von Hövel versions hailing from Germany), chief among them Carmel’s Single Vineyard from Kayoumi and the aforementioned dry version from Kishor.

Buying by Label

In addition to petroleum notes and historical references, Riesling’s marketing bid for popularity beyond the relatively narrow band of oenophilic geeks is further hampered by the maddingly complex world of German wine labels. Like other Old World countries, German labels place great importance on terroir, granting a place of honor on the label to the wines origin, however, unlike French wines for instance, the varietal name also appears on the label. An in-depth discussion of German wine classification and labels is far beyond the scope of our already extensive newsletter, but I will briefly outline some general and basic concepts (and, if you are so inclined, you can read more about the topic here and here).

In addition to petroleum notes and historical references, Riesling’s marketing bid for popularity beyond the relatively narrow band of oenophilic geeks is further hampered by the maddingly complex world of German wine labels. Like other Old World countries, German labels place great importance on terroir, granting a place of honor on the label to the wines origin, however, unlike French wines for instance, the varietal name also appears on the label. An in-depth discussion of German wine classification and labels is far beyond the scope of our already extensive newsletter, but I will briefly outline some general and basic concepts (and, if you are so inclined, you can read more about the topic here and here).

German wine is divided into table wine and quality wine, with quality wine further divided into two types – Qualitätswein (quality wine from a specific region) and Prädikatswein (superior quality wine with specific attributes, e.g. fruity, level of sweetness). Prädikatswein typically classifies the wines accordance to five sweetness levels (actual based on the weight of the wine must, an indicator of ripeness – the precursor to sweetness levels): Kabinett  (literally quality wine intended for the winemakers cabinet, light, fruity and usually semi-sweet), Spätlese (late harvest, usually semi-sweet, heavier and fruitier than Kabinett), Auslese (very ripe, usually semi-sweet to sweet and often botrytized), Beerenauslese (select berry harvest, overripe grapes – usually botrytized) and Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA) (dry berry selection, using shriveled grapes, usually botrytized) (TBA wines are among the most highly-coveted (and expensive) of them all).

(literally quality wine intended for the winemakers cabinet, light, fruity and usually semi-sweet), Spätlese (late harvest, usually semi-sweet, heavier and fruitier than Kabinett), Auslese (very ripe, usually semi-sweet to sweet and often botrytized), Beerenauslese (select berry harvest, overripe grapes – usually botrytized) and Trockenbeerenauslese (TBA) (dry berry selection, using shriveled grapes, usually botrytized) (TBA wines are among the most highly-coveted (and expensive) of them all).

Additional important designations are trocken (dry), halbtrocken (half-dry), feinherb (off-dry), lieblich (semi-sweet) and süß (sweet). The latter two rarely make the label and all five are used to help the consumer determine how the wine will actually taste. Despite the major shift towards dryer versions of Riesling, without a Trocken designation on the label, you are not going to know whether the wine is dry, off dry or sweeter, although as a rule, Alsatian wines tend to be dryer than their German counterparts.

The Kosher Conundrum

While this newsletter spent some time celebration the breakthrough in achieving success with real Riesling, the varietal’s penetration of the kosher wine market is far from assured. In addition to all the difficulties we have discussed, kosher wine consumers suffer from a malaise that prevents them from trying new varietals with which they have little familiarity. Lastly, and looming large over all others is the widely held aversion many Jews continue to have with respect to German products, a position strongly shared by my family (this made procuring everyday items somewhat challenging growing up in Israel during the 80s when reparations where at full throttle and literally everything was sourced from Germany – from wooden pencils to public buses. While I have slightly loosened the reins on this over the years, it is exclusively limited to wine and food related items (e.g. knives and wine glasses). For those not adhering to this practice, I strongly recommend trying the new Rieslings – you are in for a treat.

While this newsletter spent some time celebration the breakthrough in achieving success with real Riesling, the varietal’s penetration of the kosher wine market is far from assured. In addition to all the difficulties we have discussed, kosher wine consumers suffer from a malaise that prevents them from trying new varietals with which they have little familiarity. Lastly, and looming large over all others is the widely held aversion many Jews continue to have with respect to German products, a position strongly shared by my family (this made procuring everyday items somewhat challenging growing up in Israel during the 80s when reparations where at full throttle and literally everything was sourced from Germany – from wooden pencils to public buses. While I have slightly loosened the reins on this over the years, it is exclusively limited to wine and food related items (e.g. knives and wine glasses). For those not adhering to this practice, I strongly recommend trying the new Rieslings – you are in for a treat.

Before moving on to the specific tasting notes, I wanted to thank all of you who joined Yossie’s Corkboard’s new Facebook Page! Last week’s posts covered my recent visits (and tastings of the new releases) to Nevo Winery, Gito Winery, Domaine Netofa, Alexander Winery, Carmel Winery and Tulip Winery. I also posted about interesting recent wine-related articles and current events like next week’s Long Island Wine Expo (to which coupon code “yossiexpo2018” gets you $10 off tickets). I hope to see you all there as it promises to be a worthy event. Please make sure to Like and Follow the page in order to stay up to date on all the amazing things happening in our wonderful world of kosher wine.

Germany

St. Urbans-Hof, Nik Weis, Gefen Hashalom, Kabinett, Riesling, Saar, Ockfener, 2016: 2016 is the third vintage of the German Nik Weis winery’s Riesling as part of the “Gefen Hashalom” collaborative project between a number of Mosel vineyards. Due to various logistical issues, this year’s version hails from the superior Ockfener Bockstein vineyard resulting in a more complex and longer aging wine (in addition to the increased price tag). Sourced from Mosel’s Saar appellation, this elegant and light-to-medium bodied wine is off dry with a near-ethereal feel to it with great acidity backing up rich fruit and layers of complex aromas and flavors that tantalize. Currently the wine needs some aerating in order to showcase its potential but allow it the time and you will be rewarded with rich notes of white stone fruit, sweet yellow plums, rich sweet orange citrus notes and warm spices on a refined and elegant nose. The palate is less viscous than the 2015 slightly sweeter vintage but is balanced by terrific crisp acidity and a depth of character that intrigues along with hints of limestone and flinty minerals. While enjoyable now, the wine will only improve over the coming years and it would be a crying shame to miss out on its expected wondrous development so be sure to stash some bottles out of range to ensure longevity. 11% AbV. Drink now through 2026, likely longer [Only in Europe / the US].

St. Urbans-Hof, Nik Weis, Gefen Hashalom, Riesling, Saar, Wiltinger, 2015: After a dry 2014, the 2015 version comes in slightly off dry but with a great uptick in quality, reflecting the far superior (i.e. colder in Mosel) vintage. Apple, yellow plum, white peaches and slate minerals are enhanced with a pleasing and slightly bitter herbal overlay, floral notes and luscious orange citrus. The medium bodied palate has more apples and citrus but adds some subtle tropical notes to the mix. Perfect balance between the crisp acidity and sweet notes make it a great pairing with a wide array of dishes, including traditionally tough-to-pair Asian cuisine. 9.5% AbV. Drink now (but make sure it gets plenty of air) through 2025 [Only in Europe / the US].

St. Urbans-Hof, Nik Weis, Gefen Hashalom, Riesling, Trocken, Saar, 2014: Rated Trocken on the dryness scale, the wine opens with voluptuous nose of apricots, peaches, quince, heather is accompanied by the “traditional” notes of petrol, with ripe tangerine, white flowers, warm spices, savory gun smoke and slightly savory notes rounding out the nose. A medium bodied and oily palate is rich and deep with slate minerals and a hint of chalky limestone, more tropical fruits and austere citrus notes rounding things out and giving the wine a lovely edginess that does a good job of balancing out the near-sweet fruit (alongside the well-balanced acidity that does its part as well). At 11.5% AbV, this is a wine that needs to be an integral part of your drinking portfolio. Definitely enjoy now, but try and put a bottle or two away and see how it ages through 2022, maybe longer (the 2015 was a much better vintage) [Only in Europe / the US].

Von Hövel, Gefen Hashalom, Riesling, Kabinett, Saar, Hütte Oberemmeler, 2015: Showcasing green plums, grapefruit, sweet tropical fruit and honeysuckle along with layered minerals and plenty of the varietal’s defining petrol notes, the wine is blessed with abundant lip-smacking acidity that frames the medium bodied and somewhat oily palate with notes of eucalyptus and mint add a pleasing nuance to the waxy fruit and warm spices (more about the von Hövel estate here). 11% AbV. Drink 2020 through 2033 [Only in Europe].

Von Hövel, Gefen Hashalom, Riesling, Kabinett, Saar, Hütte Oberemmeler, 2014: Second only to its Scharzhofberg-sourced sister below (and then only by a hair), this Kabinett Riesling is such an enjoyable wine that I’d recommend hopping a plane to France if that’s the only way you can get your hands on some (although the 2015 above is from a better vintage and a slightly better wine). Wrapped around the petrol notes for which the varietal is famous, are rich notes of white peaches, quince, sweet apple, honeyed citrus and tart lemon alongside slate mineral notes and an overlay of sweet tropical fruit awesomely balanced out by bracing acidity and a delightful salinity that adds complexity to the wine as it slowly opens I your glass to reveal more layers of complexity. Make sure to give it time to open – I enjoyed my first bottle so much, it was gone before I realized and had to force myself to go much more slowly with the second one. Really impeccably balanced and so elegant I am so looking forward to seeing how my remaining bottles evolve over the coming decade. Drink now through 2028, maybe longer [Only in Europe].

Von Hövel, Gefen Hashalom, Riesling, Kabinett, Saar, Scharzhofberger, 2014: The wine opens with a voluptuous nose loaded with sweet notes of peach, guava, mango, pineapple and green apple along with a heavy dose of spice and the varietal’s characteristic notes of petrol and flinty minerals. The medium bodied palate reflects the fruity Kabinett designation and is incredibly complex and opened up wonderfully in my glass over the four hours we had together. The viscosity is nicely balanced out by bracing acidity, which also serves to keep the dense sweet fruit and heavy spices in check. Allow the wine to open and warm in your glass and you’ll be rewarded with additional layers of candied citrus, cranberry, heather, honeysuckle, herbal notes, and more sweet tropical fruit. However it is the balance and sheer elegance of this wine as it opened that really had me excited and I look forward to enjoying the bottles I hand-carried from France over the next decade, as it continues to evolve. Sourced from one of Germany’s most highly-rated vineyards, the wine is still developing so, while enjoyable with about an hour of decanting, I’d wait another 12 months before cracking open and then enjoy through 2029, maybe longer [Only in Europe].

Alsace

Koenig, Riesling, Alsace, 2016: After years of drought (remembering the lovely 2008 version from Willm), quality Alsatian Riesling has returned Together with an expanding portfolio of wines, the last few years have seen this Alsatian kosher wine producer improve the overall quality of their wines with this wine being one of their better efforts to date (and quite a bargain as well). Lovely green apple dominates the nose with sharp floral notes, honeysuckle and flinty minerals, all continuing onto the medium-bodied palate where loads of bright citrus are added to the mix along with notes or petrol, and sweet tropical fruits including apricot, pineapple and guava. At 12% AbV, the wine is very well made and was highly enjoyable. Drink now through 2019 [Mevushal].

California

Shirah, Riesling, 2017: 2017 saw the Weiss Brothers add a number of new whites varietals to their portfolio, which like their previous experimentation with Grüner Veltliner and Furmint, are very welcome indeed. While far more mainstream than those two exotic varietals, Shirah’s 2017 additions of Sauvignon Blanc and Riesling are no less delicious. Like most other things Shirah, the wine is an extreme variation of the varietal, starting with a voluptuous nose loaded to bear with expressive tropical fruit notes of passion fruit, guava and apricot along with Mayer Lemon, grapefruit and salinity-driven flinty minerals, while avoiding the characteristic notes of kerosene that will show with time. The medium bodied palate viscous plate has a lovely elegance to it, with gobs and bracing acidity keeping the rich fruit and floral notes in line, all in great balance. Drink now through 2020, maybe longer [Only in the US].

Hagafen, White Riesling, Dry, Rancho Wieruszowski, 2014: After years of producing a few semi to sweet Rieslings (i.e. 2% RS Lake County and 4% RS Wieruszowski), Hagafen added a dry option to the mix for the 2012 vintage, which he has thankfully given a permanent slot. Like Carmel’s below, the 2014 is the best vintage to date of this wine. As with most of Hagafen’s white wines, the dual-added bonuses of being mevushal and a YH Best Buy make it required drinking for any wine lover. The wine is loaded with ripe tropical fruits including melon, guava and passion fruit while also showcasing rich honeysuckle and some summer stone fruit, all tempered by great acidity and saline minerals that give the wine a welcome edge and help make it a great match to a wide array of dishes. Crisp and refreshing, I would drink this wine every day (and sometimes do) but, like all good things, the wine is coming to an end (but thankfully the 2016 and 2017 are available. Drink Now [Mevushal / Only in the US].

Hagafen, Riesling, Dry, Rancho Wieruszowski, Napa Valley, 2016: The wine opens with a lovely nose loaded with rich tropical fruits, peach and honeysuckle, accompanied by floral notes, subtle petrol, plenty of bright citrus and some gun smoke, much of which is present on the medium bodied, citrus-laden palate where the crisp lip-smacking acidity is nicely balanced by the near-sweet fruit, sweet hay and slate mineral notes. Drink now through 2019 [Mevushal / Only in the US].

Pacifica, Evan’s Collection, Riesling, Washington, 2017: Washington State basically adopted Riesling as its primary specialty varietal ten to 15 years ago and its relative expertise with the grape is evident in this lovely inaugural release from Pacifica. Notes of tart green apple, Anjou pears and plenty of rich tropical fruits are harmoniously balanced with slate mineral notes, lovely bright citrus and honeysuckle heather with hints of lavender and petrol adding a nuanced complexity that pleases alongside the ever-so-slightly bitter orange pith. Drink now through 2020 [Mevushal / Only in the US].

Goblet, Riesling, Seneca Lake, 2017: Goblet is the label produced by Yanky Drew, the kosher winemaker at City Winery who has expanded his offerings over the years to include a wide array of varietals including Cabernet Sauvignon, Cabernet Franc, Carménère, Malbec, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Syrah, with Riesling the most recent addition to the mix. Primarily sourced from California’s Mendocino County, Yanky produces wines from around the globe, sourcing grapes from Argentina, South Africa and Chile in addition to other areas of California, including the well-known Alexander Valley (I recently visited Yanky’s Brooklyn-based winery where we tasted through his portfolio and will be penning an in-depth article shortly). The grapes for his first Riesling (which will recur for the 2018 vintage) were sourced from Seneca Lake, located in New York State’s well-regarded (especially for Riesling) Finger Lakes region known for more delicate interpretations of the grape. The regionally-typical lighter (to medium) body has lovely notes of sharp tropical fruits, blooming white flowers, creamy lemon and grapefruit pith alongside the characteristic slate minerals and just a subtle note of petrol; varietaly-correct while remaining subtle enough to avoid offending his more mainstream clientele. Sufficient acidity on the palate brightens the fruit and the mineral notes provide sufficient sophistication to intrigue the more discerning aficionados. A great first effort. Drink now (and make sure to let the wine warm up a little in the glass, otherwise you won’t get the lovely fruit on the nose) [Only in the US].

Israel

Carmel, Single Vineyard, Riesling, Kayoumi, 2014: While the 2016 is the current version, the 2014 is what is currently on the shelves in the US and what Yiftach and I tasted on my recent trip to Carmel (the 2016 still needs some time to open up). It also happens to be the wine’s best vintage to date (and the closest one to the varietal’s Germanic origins). The nose needs some time in the glass to open up and reveal the lovely summer fruits and floral notes, which join the slate minerals, cut-grass, hint of gooseberry, orange zest and a nice whiff of the varietals’ characteristic petrol. The medium bodied and elegantly structured palate maintains most of the notes, adding some dried tropical fruits and green apple to the mix while bright and crisply refreshing acidity keeps everything fresh on the palate. Complex and layered, with some lovely heft, the wine culminates in a lingering finish that pleases. Drink now through 2020.

Kishor Vineyards, Misgav Riesling, 2017: The first wine sourced from Kishor’s new Riesling vineyard, Kishor has been making “Mosel-styled” Riesling wines for a while. I recently profiled Kishor’s white blend and an in-depth article on the winery is coming shortly. Well-made, with a lovely nose of grapefruit, peach, apricot and pineapple backup up by flinty-minerals, and honeyed notes of white flowers alongside some petrol bitterness. The slightly viscous and oily medium-bodied palate has plenty of bracing acidity to back up the heftier palate with a lovely mineral-laden salinity providing complexity to the abundant and controlled fruit and floral notes. At 10% AbV, this is a thinking man’s wine that is well worth seeking out. Drink now through 2020 [Only in Israel].