Big red wines that require many years of aging may seem seasonally incongruous, but after three newsletters covering summer basics like white wine, rosé and grilled food wine pairing I thought it might be a good idea to follow Bruce Willis’ creed of “always being prepared.” So in order to ensure we are all properly prepared for the chagim and accompanying colder weather just around the corner, this week’s newsletter focuses on appropriate wines for the coming season – namely French wines. In this week’s newsletter (and to honor France’s recent Mondial win), we focus on Bordeaux – the heart of French wine.

Know Thy History

After a decade spent hiding in the shadows, the popularity of French wine among the kosher consumer is once again on the rise. While partially attributable to the wine’s growing penetration of the mainstream kosher market, much of the genre’s current success stems from a reversal of the blows French wine took over a decade ago. Starting with the 1997 vintage, the kosher wine market benefited from a string of successful kosher vintages with each subsequent year adding increasingly higher-end options to the expanding portfolio. By the time the 2005 vintage was dubbed “vintage of the century”, the kosher wine market was frothy as can be and the holy grail of kosher First Growths seemed just around the – and then it all came crashing down.

When it all went Wrong

A general hostility towards France as a result of its opposition to the Iraq War rapidly coalesced around French products, with a focus on those most-closely associated with France – perfume, cheese and of course, wine. Given the war’s perceived importance to Israel’s security, the kosher market took its boycott of French wine to extreme levels, a measure that greatly benefited Israeli wine which enjoyed a huge resurgence during this time.

A general hostility towards France as a result of its opposition to the Iraq War rapidly coalesced around French products, with a focus on those most-closely associated with France – perfume, cheese and of course, wine. Given the war’s perceived importance to Israel’s security, the kosher market took its boycott of French wine to extreme levels, a measure that greatly benefited Israeli wine which enjoyed a huge resurgence during this time.

While certain producers bailed on their commitments creating a terrible chilul hashem and resulting in a widespread reluctance by the various French wineries to make additional kosher runs (an issue that only now (and very slowly) seems to be abating), most producers stuck to their commitments. With production at peak levels and long-term contracts in place, the global financial crisis was simply the (huge) final nail in the coffin. The tristate area represents kosher wine’s largest market, with Wall Street fueling the bulk of its higher-end and segment of kosher wine buyers hit the hardest by the drop in financial wherewithal. Even the magnificent wines of the 2005 vintage couldn’t overcome the culmination of punishing trends and wines piled up in warehouses and grew dusty on retailer shelves across the country. The situation was also the cause behind the kosher wine market missing Bordeaux’s magnificent 2009 and 2010 vintages with only a few exceptions (e.g. 2009 Smith Haut Lafite and 2010 Haut Condissas) and fed the recalcitrance of French producers to make additional kosher runs for many years.

Le Revers de la Fortune

As global markets recovered and hatred of all things French subsided over the last few years we have seen a major resurgence of kosher French wine. Starting with the mediocre 2013 vintage, importers have been increasing their French wine portfolios with each subsequent vintage, benefiting from vintages that seem to get better every year a market with seemingly endless capacity for annual price increases approaching 25%.

Seeing is Believing

With all these changes on the horizon I felt it was time to see things with my own eyes so earlier this year I was fortunate to have been afforded the rare opportunity to visit some of the château currently producing kosher wines (including a very special day spent at Champagne Drappier). While the logistics of kosher wine production doesn’t typically allow for regular visitation at these wineries, the largest producer/importer of kosher French wine – Royal Wine graciously accommodated my request and arranged for a tour through some of their portfolio of châteaux (as per my custom, I paid for my entire trip). I was lucky to be accompanied by Menachem Israelievitch, (Royal’s European kosher winemaker who works with the various châteaux on the kosher wine production) who graciously drove me around and ensured a successful tasting. A big thank you is due to the various châteaux for their time and generous hospitality, to Royal Wine for providing me with the opportunity and to Menachem for his generous allocation of time while chauffeuring me around and answering all my questions, the result of which are included in this week’s newsletter.

With all these changes on the horizon I felt it was time to see things with my own eyes so earlier this year I was fortunate to have been afforded the rare opportunity to visit some of the château currently producing kosher wines (including a very special day spent at Champagne Drappier). While the logistics of kosher wine production doesn’t typically allow for regular visitation at these wineries, the largest producer/importer of kosher French wine – Royal Wine graciously accommodated my request and arranged for a tour through some of their portfolio of châteaux (as per my custom, I paid for my entire trip). I was lucky to be accompanied by Menachem Israelievitch, (Royal’s European kosher winemaker who works with the various châteaux on the kosher wine production) who graciously drove me around and ensured a successful tasting. A big thank you is due to the various châteaux for their time and generous hospitality, to Royal Wine for providing me with the opportunity and to Menachem for his generous allocation of time while chauffeuring me around and answering all my questions, the result of which are included in this week’s newsletter.

The Heart of French Wine

While I will discuss specific details from the five wineries we visited (Château Léoville-Poyferré, Château Clark, Château Tertre, Château Malartic and Champagne Drappier), the first part of the newsletter is going to discuss French wine in general, with a specific focus on Bordeaux as representing some of the best the country has to offer. We are also going to discuss a number of issues specific to the production of kosher wine in France, but before we do that, a few words on Bordeaux and its prestigious position at the top of the wine world is in order

Word Gets Around

Truth be told, the age-old real estate adage suffices to really explain what makes Bordeaux so unique – location, location and location (geopolitical and geographical). Likely introduced to the region by the conquering Romans in middle of the first century, wine production has continued unabated since that time. Bordeaux’s position as a major port city led it to become synonymous with global trade and introduced major prosperity to the city and its merchants. Easy access to ships traveling towards the world’s aristocracy and nobility. Following in their footsteps, the wealthy classes of Old Europe (primarily in Great Britain starting in 12th century onward and the Netherlands starting in the 17th century) started collecting and aging the wines, thus cementing Bordeaux’s status as the wines of the upper class. However, the primary reason it has endured as the world’s primeur wine-growing region is terroir (the ultimate multi-meaning French word that incorporates soil, elevation and climate as they are relate to growing grapes intended for wine). Bordeaux’s terroir is as perfect as can be, with the surrounding region appearing to have been created solely for the purpose of growing the best wine-producing grapes the world has ever seen.

Truth be told, the age-old real estate adage suffices to really explain what makes Bordeaux so unique – location, location and location (geopolitical and geographical). Likely introduced to the region by the conquering Romans in middle of the first century, wine production has continued unabated since that time. Bordeaux’s position as a major port city led it to become synonymous with global trade and introduced major prosperity to the city and its merchants. Easy access to ships traveling towards the world’s aristocracy and nobility. Following in their footsteps, the wealthy classes of Old Europe (primarily in Great Britain starting in 12th century onward and the Netherlands starting in the 17th century) started collecting and aging the wines, thus cementing Bordeaux’s status as the wines of the upper class. However, the primary reason it has endured as the world’s primeur wine-growing region is terroir (the ultimate multi-meaning French word that incorporates soil, elevation and climate as they are relate to growing grapes intended for wine). Bordeaux’s terroir is as perfect as can be, with the surrounding region appearing to have been created solely for the purpose of growing the best wine-producing grapes the world has ever seen.

Earth, Air, Fire and Water

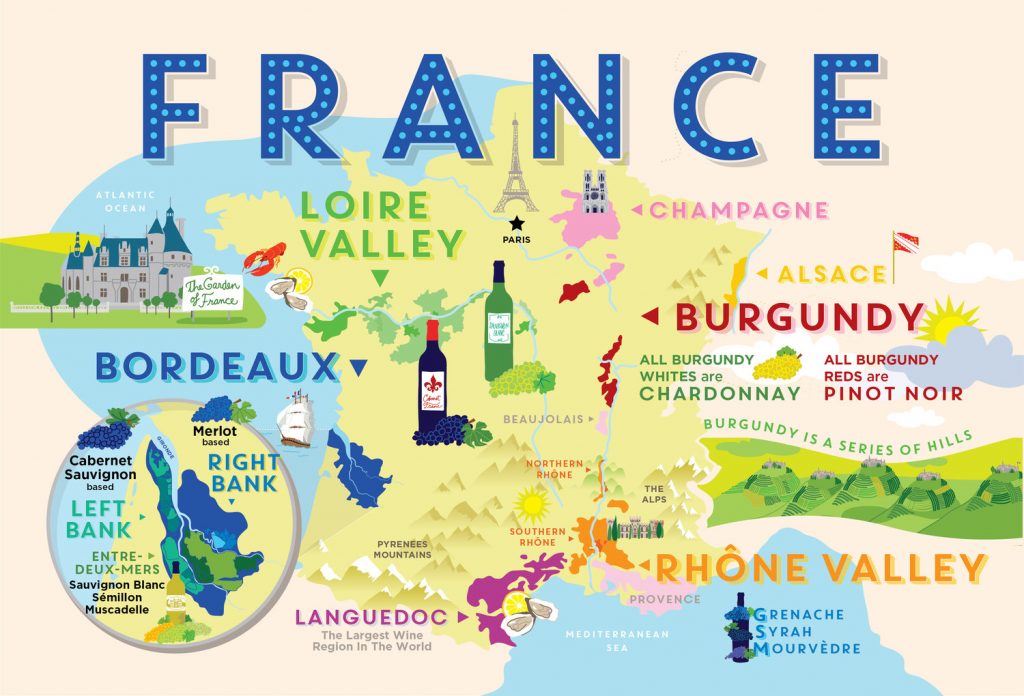

So what exactly is Bordeaux wine (besides obviously being wine produced in the Bordeaux region of France)? Unlike wines produced in the United States, Israel and other “New World” wine producing countries, France and other Old World countries label their wines according to the region in which they are produced and not the varietal of grape used (e.g. Tempranillo grown in the Rioja region of Spain will be labeled as “Rioja” while American Tempranillo will be labeled as “Tempranillo”). Very few Bordeaux wines are pure varietal wines, but rather a blend blends of the so-called Noble Grapes. Historically only six varietals were deemed Noble – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc, but over time additional varietals were deemed worthy (e.g. Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Semillon). While Bordeaux produces many top-tier white blends and dessert wines (including the be-end-all Château d’Yquem), it is primarily known for its carefully blended red wines.

So what exactly is Bordeaux wine (besides obviously being wine produced in the Bordeaux region of France)? Unlike wines produced in the United States, Israel and other “New World” wine producing countries, France and other Old World countries label their wines according to the region in which they are produced and not the varietal of grape used (e.g. Tempranillo grown in the Rioja region of Spain will be labeled as “Rioja” while American Tempranillo will be labeled as “Tempranillo”). Very few Bordeaux wines are pure varietal wines, but rather a blend blends of the so-called Noble Grapes. Historically only six varietals were deemed Noble – Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, Riesling and Sauvignon Blanc, but over time additional varietals were deemed worthy (e.g. Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Semillon). While Bordeaux produces many top-tier white blends and dessert wines (including the be-end-all Château d’Yquem), it is primarily known for its carefully blended red wines.

Rules and Regulations

With wine so-closely tied to France’s identity, over the years French authorities have instituted a plethora of laws intended to protect the industry and maintain the quality of wine necessary for Bordeaux’s continued dominance. Chief among these laws are those pertaining to Appellation d’origine controlee (“AOC”) – protected designation of origin); which dictate how wines can be labeled, marketed and sold (other French agriculture products like cheese and butter are also subject to these same rules). The country’s wine producing regions are divided into many regions and sub-regions and each one carries its own set of rules of what can and cannot go into the wine in order to carry the specific AOC designation. Additionally, in order to be deemed a Bordeaux-blend, the wine needs to include Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot but can also legally include Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carménère.

With wine so-closely tied to France’s identity, over the years French authorities have instituted a plethora of laws intended to protect the industry and maintain the quality of wine necessary for Bordeaux’s continued dominance. Chief among these laws are those pertaining to Appellation d’origine controlee (“AOC”) – protected designation of origin); which dictate how wines can be labeled, marketed and sold (other French agriculture products like cheese and butter are also subject to these same rules). The country’s wine producing regions are divided into many regions and sub-regions and each one carries its own set of rules of what can and cannot go into the wine in order to carry the specific AOC designation. Additionally, in order to be deemed a Bordeaux-blend, the wine needs to include Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot but can also legally include Cabernet Franc, Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carménère.

Telling Right from Left

The large Bordeaux region is colloquially divided into two regions – the Left Bank and the Right Bank, while legally divided into 54 different appellations (named after the city, town or village around which the vineyards are typically situated). The Right and Left Bank designation is based on which side of the Gironde River the vineyards are located, while the area located between the Gironde and Dordogne Rivers is designated “between the two seas”. Generally speaking, Right Bank wines’ primary varietal is Merlot while Left Bank blends have a majority of Cabernet Sauvignon. The Left Bank is sub-divided into two regions – Graves (upstream from the City of Bordeaux) and Médoc (downstream from the City of Bordeaux which is where the vast majority of the best wines are produced excluded Sauternes which is in Graves) and contains a much higher percentage of the more prestigious châteaux. Some well-known Left Bank appellations include Saint-Julian (Château Léoville Poyferré), Pessac-Leognan (Châteaux Smith-Haut-Lafite) Saint-Estèphe (Château Lafon-Rochet), Haut-Médoc (Barons Edmond et Benjamin de Rothschild), Margaux (Château Giscours), and of course Sauternes (Château La Tour Blanche). Well-known Right Bank appellations include Pomerol (Domaine Roses Camille) and Saint-Émilion (Château de Valandraud).

Class Reigns Supreme

While most of the world has moved towards a merit-based ranking (in all aspects), Bordeaux (and many other Old World wine-producing countries) continues to determine the prestige (and resulting economics) of its châteaux by stubbornly adhering to a classification system that takes other factors into account as well. The primary system is the Official Classification of 1855 which was created for the 1855 Paris exposition at the behest of Napoleon who wanted a ranking for the best wines of Bordeaux to be showcased at the exposition for the entire world to see. Wine brokers and merchants from around the world were asked to rank the wines, which they did according to reputation and price – then considered factors directly correlating to quality. The wines were ranked from first to fifth growths, with all of the wines coming from the Left Bank and only one red wine coming from Graves (the rest hailed from the Médoc). Even though they were deemed far inferior to red wines at that time, white wines received their own, separate qualification, with the highest ranking called “Superior First Growth” (Premier Cru Superior) and allocated only to one wine – Château d’Yquem. While we await a kosher d’Yquem, we get to enjoy four different First Growth (one run down the ladder) – Sauternes, all of which I have reviewed and recommended – Château La Tour Blanche (2014), Château Clos Haut-Peyraguey (2014), Château de Rayne-Vigneau (2014) and Château Guiraud (1999-2001, 2016).

While most of the world has moved towards a merit-based ranking (in all aspects), Bordeaux (and many other Old World wine-producing countries) continues to determine the prestige (and resulting economics) of its châteaux by stubbornly adhering to a classification system that takes other factors into account as well. The primary system is the Official Classification of 1855 which was created for the 1855 Paris exposition at the behest of Napoleon who wanted a ranking for the best wines of Bordeaux to be showcased at the exposition for the entire world to see. Wine brokers and merchants from around the world were asked to rank the wines, which they did according to reputation and price – then considered factors directly correlating to quality. The wines were ranked from first to fifth growths, with all of the wines coming from the Left Bank and only one red wine coming from Graves (the rest hailed from the Médoc). Even though they were deemed far inferior to red wines at that time, white wines received their own, separate qualification, with the highest ranking called “Superior First Growth” (Premier Cru Superior) and allocated only to one wine – Château d’Yquem. While we await a kosher d’Yquem, we get to enjoy four different First Growth (one run down the ladder) – Sauternes, all of which I have reviewed and recommended – Château La Tour Blanche (2014), Château Clos Haut-Peyraguey (2014), Château de Rayne-Vigneau (2014) and Château Guiraud (1999-2001, 2016).

No Winds of Change

This classification reigns supreme even today and has been changed only twice in its 160 year history. Château Cantemerle was added as a fifth growth in 1856 and, after decades of extensive lobbying by the powerful Philippe de Rothschild, Château Mouton Rothschild was elevated from a second growth to a first growth in 1973. While no kosher first growth wines have been made, a number of second growth (and lower) wines exist including Château Rauzan-Gassies (Margaux), Château Léoville-Poyferré (St.-Julien), Château Gruaud-Larose (St.-Julien) and Château Lascombes (Margaux).

This classification reigns supreme even today and has been changed only twice in its 160 year history. Château Cantemerle was added as a fifth growth in 1856 and, after decades of extensive lobbying by the powerful Philippe de Rothschild, Château Mouton Rothschild was elevated from a second growth to a first growth in 1973. While no kosher first growth wines have been made, a number of second growth (and lower) wines exist including Château Rauzan-Gassies (Margaux), Château Léoville-Poyferré (St.-Julien), Château Gruaud-Larose (St.-Julien) and Château Lascombes (Margaux).

Since 1855 most of the classed châteaux have undergone changes that lead to their division (as the properties divided up to be passed on to the next generation) and/or expansion (as they are bought and sold like any other highly-priced asset). As a result, a classed property from 1855 may be split into three different estates today, each carrying the prestigious Cru Classé designation. One of the (many) peculiarities of Bordeaux is that any château can use any parcel within its boundaries, regardless of quality (so a first growth château can buy a bordering plot of lessor quality and label the resulting wine under its prestigious title (legally permitted but practically unlikely given the risk of diminishing the quality). All the wines included in the 1855 Classification carry the title of Cru Classé (Classed Growths) with the first growths referred to as “Premiers Crus”.

Many in the industry have long railed against the 1855 Classification as outdated and not accurately reflecting quality (one example would be the fifth growth Pontet-Canet whose stature has skyrocketed recently after a few years of perfect and near-perfect scores from Robert Parker). Over the years many attempts have been made to institutionalize a new method of classification but not have stuck. As globalization spread and Bordeaux’s fame spread to every corner of the earth, additional rankings were created during the middle of the 20th century for other regions including Graves and Saint- Émilion, but none carry the weight of the 1855 Classification. Other, lower-ranked Médoc châteaux carry the title of Cru Bourgeois (a designation banned in 2007 and reinstated in 2010), including Château Labégorce Zédé for which there is a kosher run.

Built for the Long Haul

Among Bordeaux’s many claims to fame is the wine’s ability to age for decades, while evolving throughout the years, with evolution being more desirable than surviving (i.e. wines that stay the same but last a long time are less interesting than those that change and mature over time). We have previously discussed aging and there are a number of factors that help Bordeaux wines achieve such longevity. Bordeaux’s focus on the highly-tannic Cabernet Sauvignon is a big factor, as is the requisite oak-aging for Bordeaux blends. Tannins are a fundamental component to long-term aging and they are imparted to the wine both from the grape skins and the oak barrels, with French oak having a much higher percentage of tannins than American oak. The high acidity prevalent in the cooler region is another contributing factor, as is the age of the vineyards. As vines age their yield drops, focusing the flavors on a smaller number of grapes per vine. As a result, older vines yield grapes of higher intensity and greater complexity.

Among Bordeaux’s many claims to fame is the wine’s ability to age for decades, while evolving throughout the years, with evolution being more desirable than surviving (i.e. wines that stay the same but last a long time are less interesting than those that change and mature over time). We have previously discussed aging and there are a number of factors that help Bordeaux wines achieve such longevity. Bordeaux’s focus on the highly-tannic Cabernet Sauvignon is a big factor, as is the requisite oak-aging for Bordeaux blends. Tannins are a fundamental component to long-term aging and they are imparted to the wine both from the grape skins and the oak barrels, with French oak having a much higher percentage of tannins than American oak. The high acidity prevalent in the cooler region is another contributing factor, as is the age of the vineyards. As vines age their yield drops, focusing the flavors on a smaller number of grapes per vine. As a result, older vines yield grapes of higher intensity and greater complexity.

Familiarity Shouldn’t Breed Contempt

Another benefit of older vines is that the grower has achieved a higher level of familiarity with the plot and knows exactly what needs to be done to coax the absolute best product out of the land. The Bordelaise wine growers have been planting the same varietals in the same plots of land for centuries and have fine-tuned to an exact degree exactly what works where and why. While nearly all of the French vineyards were destroyed during the mid-19th century phylloxera infestation (and were reconstituted by grafting European vines onto American phylloxera-resistant rootstock), the knowledge and expertise remained and greatly benefits the industry to this day. As any winemaker worth his salt will tell you – “great wine starts (or is made) in the vineyard”, so knowing what works best for each plot of land has immense value in coaxing the best wine out of the ground. Compare that to the few decades (at best) of experience Israeli and California wine growers have and you’ll realize there is still plenty of room for improvement on the already terrific progress we have made. With experimentation in their very distant past, French wineries are content to churn out the same few wines every year as representative of the absolute best their land has to offer where Israeli wineries are still in the exploration phase of learning the best grapes for the various plots of land (while also dealing with constant consumer clamoring for something new).

However, even the French are susceptible to change and, as global warming continues to heat things up, Bordeaux’s style is impacted by the hotter climate and is producing slightly riper wines that are approachable far earlier than in the past (the impact on their long-term aging ability remains to be seen).

The Kosher Conundrum

While we are blessed with many top notch kosher Bordeaux wines, there are no kosher wineries in Bordeaux. Rather, the various châteaux produce kosher runs of certain wines within their portfolio, nearly always at the behest of a kosher importer. While many of these kosher runs are excellent and can qualitatively match their non-kosher brethren, they will never be exactly the same wine (despite bearing the nearly identical label). . The reason for this is due to the actual mechanics in how kosher wines are made at non-kosher wineries and usually results in a different blend than the non-kosher version. With the château’s name on the bottle its reputation is tied to how the resulting wine turns out, so obviously the château does its best to ensure that the kosher version adheres as best possible to winery’s style and closely resembles the wine in question (even though the production method is different).

While we are blessed with many top notch kosher Bordeaux wines, there are no kosher wineries in Bordeaux. Rather, the various châteaux produce kosher runs of certain wines within their portfolio, nearly always at the behest of a kosher importer. While many of these kosher runs are excellent and can qualitatively match their non-kosher brethren, they will never be exactly the same wine (despite bearing the nearly identical label). . The reason for this is due to the actual mechanics in how kosher wines are made at non-kosher wineries and usually results in a different blend than the non-kosher version. With the château’s name on the bottle its reputation is tied to how the resulting wine turns out, so obviously the château does its best to ensure that the kosher version adheres as best possible to winery’s style and closely resembles the wine in question (even though the production method is different).

Getting Down to Brass Tacks

In order to understand the difference, a brief primer on how these wines are made can be helpful. Most Châteaux grow three to five different varieties of grapes for their blends. Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot will always be present along with some or all of Petit Verdot, Cabernet Franc and Malbec. Each of these varieties ripens at a different time and different plots ripen at different paces, resulting in a multitude of harvest times, spread across a few weeks. Not only are the different varietals picked at different times, often different areas (or parcels) within any given vineyard or plot are harvested at different times, as they ripen at their own pace (such differentiation can go all the way to a single row of vines). Once harvested, each batch of grapes is fermented and aged separately, only meeting each other in the spring, when the initial blending occurs in advance of the uber-important en premier (the method in which nearly all Bordeaux wine is bought and sold). While the winemaker will taste and evaluate the wine frequently between those two times, the blending process is a more comprehensive event that typically occurs over a few days and is when winemakers make the macro-level decisions as to the likely blend). The winemaker has immense flexibility as to when each lot is picked, fermented and blended, allowing him to choose the absolute best representation of the Château’s production in any given year.

The Devil is in the Details

First, contracts for the kosher runs are done over a year in advance of actual harvest and specific plots are allocated by the château for this purpose so, even in the infrequent occasions were a proportionate ratio all of the varieties going into the blend are allocated for the kosher run, the kosher run will be a snapshot of the specific plots, parcels or vines while the regular version will be a blend across all of the rest of the grapes (yielding a different but not necessarily better or worse wine). Additionally, the kosher requirement that only Orthodox Jews handle the wine post-picking adds additional complications and further constrains the winemaker’s ability in making those determinations for the kosher run, especially the ability to pick each varietal in at exactly the right time. . Like most non-Israel wine-producing countries, the availability of qualified Orthodox folk is relatively sparse and most of them will work at more than one winery (which limits the amount of time they can allocate to any specific winery, where all the other workers are full-time employees). Being Sabbath-observant also limits the times in which the grapes can be picked and harvest-season’s chag-concentrated period between Rosh Hashana and Simchat Torah further complicates matters and can often result in less than optimum picking times for the kosher-ordained plots.

First, contracts for the kosher runs are done over a year in advance of actual harvest and specific plots are allocated by the château for this purpose so, even in the infrequent occasions were a proportionate ratio all of the varieties going into the blend are allocated for the kosher run, the kosher run will be a snapshot of the specific plots, parcels or vines while the regular version will be a blend across all of the rest of the grapes (yielding a different but not necessarily better or worse wine). Additionally, the kosher requirement that only Orthodox Jews handle the wine post-picking adds additional complications and further constrains the winemaker’s ability in making those determinations for the kosher run, especially the ability to pick each varietal in at exactly the right time. . Like most non-Israel wine-producing countries, the availability of qualified Orthodox folk is relatively sparse and most of them will work at more than one winery (which limits the amount of time they can allocate to any specific winery, where all the other workers are full-time employees). Being Sabbath-observant also limits the times in which the grapes can be picked and harvest-season’s chag-concentrated period between Rosh Hashana and Simchat Torah further complicates matters and can often result in less than optimum picking times for the kosher-ordained plots.

Other complications stem from a limited number of fermentation containers for the kosher run, as each needs to be cleaned, koshered and specially prepared for the kosher run (many of the châteaux have containers specially tailored for each plot, an advantage the kosher runs simply do not have). In addition to losing the ability to specifically tailor each parcel to its perfect production, the winemaker often needs to co-ferment certain varietals which can inhibit the development of each varietals individual characteristics. Co-fermentation can be a positive thing if all the co-fermenting grapes have ripened to (more or less) the same degree but as discussed below, the need to cluster harvesting together in colder climates like Bordeaux can result in certain varieties being picked too early.

Turning a Corner

However things are changing and with a growing appreciation and appetite for top-quality wines, more resources are being put towards matching the kosher runs to their non-kosher siblings. According to Menachem, the 2015 Château Léoville-Poyferré is the closest Bordeaux blend ever to the regular version, a feat accomplished by the unprecedented contracting for a pro-rata percentage of each and every parcel used by the winery in their Grand Vin (which provided Menachem and Léoville’s winemaker with the same raw materials for the kosher run as used in the non-kosher one (while I can’t vouch for the similarity, it’s certainly one of the vintage’s best wines and highly recommended). While Royal’s European winemaker Menachem Israelivitch is heavily involved in each aspect of production, the winemaker at each château still makes the blending and aging decisions (together with Menachem) and the château owner obviously needs to be satisfied as to the quality and style before he agrees to put his label on the wine.

My only point here is that kosher wines are different wines than their non-kosher counter-parts, despite periodic attempts to obfuscate this fact by using the non-kosher wine’s scores and reviews to promote the kosher run. Even though different nearly always means inferior (due to the reasons listed above), the good wines are still very good and well-worth your effort and hard-earned shekels (a differentiation relevant mostly when comparing the higher pricing of the kosher version; the next topic of our discussion).

My Wine is too Darn High[ly Priced]

Given its stature, it shouldn’t be surprising that the best Bordeaux wines command astronomical prices (some first growths are approaching $1,000 a bottle). However, as the largest wine-producing region of France, there are plenty of more affordable options among the thousands of wines produced. As the kosher French wine market continues to grow, we are seeing many more options than ever before and these run the entire gamut of prices as well (although with no kosher first growths, $300 is the current ceiling for newly released wines). That said, I often hear complaints about the disparate pricing between the kosher and non-kosher versions, where the kosher version will often be priced between 60-200% higher than its non-kosher peer (a pricing discrepancy that doesn’t exist in Israel, where kosher and non-kosher wines are equally expensive).

Given its stature, it shouldn’t be surprising that the best Bordeaux wines command astronomical prices (some first growths are approaching $1,000 a bottle). However, as the largest wine-producing region of France, there are plenty of more affordable options among the thousands of wines produced. As the kosher French wine market continues to grow, we are seeing many more options than ever before and these run the entire gamut of prices as well (although with no kosher first growths, $300 is the current ceiling for newly released wines). That said, I often hear complaints about the disparate pricing between the kosher and non-kosher versions, where the kosher version will often be priced between 60-200% higher than its non-kosher peer (a pricing discrepancy that doesn’t exist in Israel, where kosher and non-kosher wines are equally expensive).

As alluded to above, much of the price disparity relates to the extra costs of kosher wine production. As discussed, there is substantial additional costs in sourcing qualified Orthodox personnel for the work as they are only there for the specific purpose of creating the kosher run, they are added labor on top of the winery’s existing crew (as opposed to Israel and California where they are full time employees who occupy “regular” positions at the winery, eliminating any such redundancies).

Higher margins are also in effect to compensate the producers for the significantly elevated risk levels involved in undertaking kosher runs but they are also implemented because they can be. Regardless of how hard we all romanticize wine, it is a business like any other and the laws of supply and demand are in effect just like any other business. The rapid expansion of the kosher wine market, increasing levels of disposable income and a limited supply of available wine options (which in turn are typically produced in relatively low quantities) create the perfect breeding ground for a high margin product – perceived luxury in extremely limited quantities. As the market expands it will become more competitive and folks will have more options where to spend their money; but for now, if we want to enjoy those amazing high-end Bordeaux wines, we need to pay dearly for them. Remember that the producer/importer took a big risk in making these wines and the only way they will keep making these wines we so desperately crave is to provide a solid business case for the endeavor – by acquiring them. Another thing to remember is that, even in our current limited market, there are some mid-range and well-priced options (e.g. Moulin Riche and Royaumont) and some with terrific QPR (e.g. Fourcas Dupré) and many of the more expensive wines (e.g. Lascombes and Grand-Puy Ducasse (both on my Best of 2017 list)), are worth the money (if you can afford it)

Color and Country-Strong

Mirroring the general consumption trends of the kosher wine market, the vast majority of kosher French runs are red blends (excluding Champagne and Sauternes). There were some great white wines made in the early 00’s but the market wasn’t there yet and it took a long time to sell out the expensive Montrachet (Burgundy Chardonnay) and Pouilly Fumé (Loire Sauvignon Blanc). Many of the 2004 whites suffered from the same premature oxidation issues (premox) as the regular market, giving the French white wines another blow from which they are only recently recovering. While the white wines of Bordeaux aren’t considered on the same level as those hailing from Burgundy, there are some very nice options currently available from many other regions (e.g. Chablis in Burgundy and Sancerre in the Loire Valley) and a number of worthy white Bordeaux options just around the corner – stay tuned.

Mirroring the general consumption trends of the kosher wine market, the vast majority of kosher French runs are red blends (excluding Champagne and Sauternes). There were some great white wines made in the early 00’s but the market wasn’t there yet and it took a long time to sell out the expensive Montrachet (Burgundy Chardonnay) and Pouilly Fumé (Loire Sauvignon Blanc). Many of the 2004 whites suffered from the same premature oxidation issues (premox) as the regular market, giving the French white wines another blow from which they are only recently recovering. While the white wines of Bordeaux aren’t considered on the same level as those hailing from Burgundy, there are some very nice options currently available from many other regions (e.g. Chablis in Burgundy and Sancerre in the Loire Valley) and a number of worthy white Bordeaux options just around the corner – stay tuned.

Like most wine producing countries where much of the production never makes it out of the country, there is far more kosher French wine available in France (and other parts of Europe) than on US shelves. However among the many anomalies within the kosher wine market (and like Israeli wines), the vast majority of better kosher options make their way to our shelves. With the lion’s share of the kosher wine market located in the tristate area of the United States, the various kosher wine importers work tirelessly to ensure that the best stuff makes its way here (producers are also active in trying to get their best stuff to their largest potential market). If you wander into a kosher store in Paris you will be greeted with dozens of unrecognizable kosher wine options to choose from, much of it plonk. On a recent trip to France, I purchased and tasted 36 different wines off the shelves of kosher retailers and only found 6 wines worthy of my attention. Notwithstanding these facts, many additional kosher wines don’t make their way out of Europe, leaving visitors with some nice options for treasures to bring home, especially in the cheaper range (Decent options priced at $8-15 in France are no longer worthy at the ~$25 they appear at on US shelves). Another thing to keep in mind is that many of the wines that are mevushal in the US are sold as non-mevushal (and usually better / more interesting) in Europe (e.g. Château Le Crock), which also makes for some very interesting comparative tasting opportunities).

Seeing is Believing

With that not-so-brief primer on Bordeaux and some of its kosher-specific peculiarities, we can now delve into the specifics of the five lovely wineries I visited with Menachem Israelivitch on my recent trip to Bordeaux: Château Léoville-Poyferré, Château Clark, Château Tertre, Château Malartic and Champagne Drappier.

I. Château Léoville-Poyferré

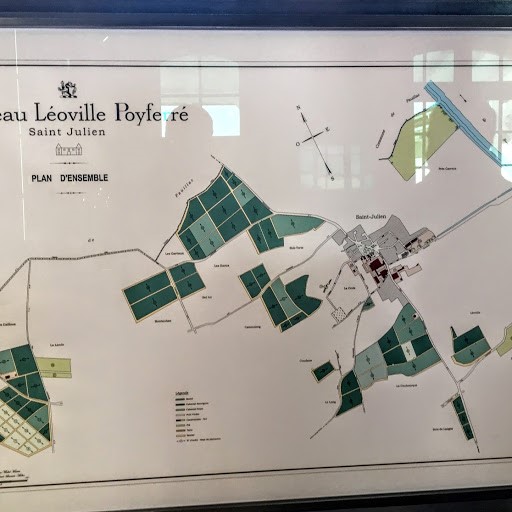

Our first stop was at the famed Château Léoville-Poyferré, located in the Saint Julian region of the Médoc appellation, long one of the top kosher French wines available (the 1999 was a constant anniversary accompaniment as I was married that year). Originally part of the much larger Léoville estate whose origins trace back to 1638 and was, at one point, the largest estate in the entire Médoc. Classified as a Second Growth in the 1855 Classification, today’s Léoville-Poyferré is one of the three individual estates resulting from Léoville’s fragmentation over the years (the other two are Léoville Barton and Léoville-Las Cases). The estate has been owned by the Cuvelier family since 1920 and they also own Château Le Crock and Moulin Riche. While Le Crock is a separate winery located in nearby Saint-Estèphe (acquired by the Cuvelier’s before Léoville in 1903), Moulin Riche is a neighboring parcel that produced Léoville’s second wine until the incredible 2009 when the family determined to grant it its own designation (although it’s not an independent winery – all the production is done at Léoville-Poyferré). Following this designation, Pavillion Poyferré was designated as the joint second wine of the two “estates” (i.e. the wine is a blend of younger vines located plot of a lessor quality located further from the river).

Our first stop was at the famed Château Léoville-Poyferré, located in the Saint Julian region of the Médoc appellation, long one of the top kosher French wines available (the 1999 was a constant anniversary accompaniment as I was married that year). Originally part of the much larger Léoville estate whose origins trace back to 1638 and was, at one point, the largest estate in the entire Médoc. Classified as a Second Growth in the 1855 Classification, today’s Léoville-Poyferré is one of the three individual estates resulting from Léoville’s fragmentation over the years (the other two are Léoville Barton and Léoville-Las Cases). The estate has been owned by the Cuvelier family since 1920 and they also own Château Le Crock and Moulin Riche. While Le Crock is a separate winery located in nearby Saint-Estèphe (acquired by the Cuvelier’s before Léoville in 1903), Moulin Riche is a neighboring parcel that produced Léoville’s second wine until the incredible 2009 when the family determined to grant it its own designation (although it’s not an independent winery – all the production is done at Léoville-Poyferré). Following this designation, Pavillion Poyferré was designated as the joint second wine of the two “estates” (i.e. the wine is a blend of younger vines located plot of a lessor quality located further from the river).

The estate grows Cabernet Sauvignon (~61%), Merlot, Petit Verdot and Cabernet Franc and the total annual (across the three wines) of 400,000 bottles annually is approximately 55% for the Léoville-Poyferré, 15-25% for the Moulin Riche with the Pavillon rounding out the rest. In addition to being sourced from different plots, each of the three wine are also produced using different techniques with Léoville-Poyferré aged in 80% new French  oak, Moulin Riche in 20% new oak and Pavillon aged solely in the 2nd-year barrels of both wines.

oak, Moulin Riche in 20% new oak and Pavillon aged solely in the 2nd-year barrels of both wines.

Production-wise, the tanks and barrels are of all different sizes as the winery tailors them to each specific plot and wine. Special conical tanks are used in fermenting the Léoville to provide greater extraction and enable the winemaker to use only the pump-over (as opposed to punch-down) technique. The château acquired an expensive optical sorter in 2011 (which is used to sort the grapes following the more traditional careful hand-sorting and helps ensures only the highest-quality grapes are used).

With common ownership across the properties, Royal Wine has been able to produce kosher cuvees of all four wines on a regular (if not annual) basis (Le Crock, Léoville-Poyferré, Pavillon de Léoville-Poyferré and Moulin Riche). The Léoville-Poyferré was first made kosher for the 1995 vintage followed by 1999-2003, 2005 and then 2015 and 2017 (2015 is currently on the market). Pavillon was first made as a kosher run for the 2012 vintage, skipped the less-than-optimal 2013 vintage and has then consecutively since 2014. Moulin Riche was first made for the 2011 vintage and then every other year – 2013, 2015 and 2017 (Royal produced all four wines (3 Léoville and Le Crock) for the 2017 vintage (Le Crock was first made kosher for the 2001 vintage followed by 2003, 2005, 2012 and now 2015-2017). While each component of the regular Léoville spends six months in oak before being blended around March-April for the en primeur and another 12 months or so in oak as a final blend, the kosher run is blended at harvest and aged in oak only as the final blended wine. However, as noted above, 2015 was the first time that Royal contracted for a pro-rata portion of all the parcels and varietals, which enabled them to produce as close to identical a kosher run as ever before. Compare the regular blend of 65% Cabernet Sauvignon, 26% Merlot, 5% Cabernet Franc and 3% Petite Verdot with the kosher blend of 64% Cabernet Sauvignon, 28% Merlot, 3% Cabernet Franc and 6% Petite Verdot and you will see how close they came, at least varietal-wise.

Following a tour of the winery, Menachem and I were joined in the very cool tasting room by Léoville’s head winemaker Isabelle Davin and Cellar Master Didier Thomann for some barrel

Following a tour of the winery, Menachem and I were joined in the very cool tasting room by Léoville’s head winemaker Isabelle Davin and Cellar Master Didier Thomann for some barrel  tastings. An entire wall of the tasting room is covered with the signatures of the entire whose who of the wine world, including Robert Parker, Jancis Robinson and Hugh Johnson. In addition to the star-studded team, the Château also utilizes the services of famed flying winemaker Michel Rolland who, together with the winemaking team and Menachem (for the kosher version) compile the blend. We tasted barrel samples of the 2016 Pavillon (a blend of 67% Cabernet Sauvignon and 33% Merlot (at 60+ years-old, all the Petit Verdot is designated for the higher wines)) and 2016 Le Crock (64% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot and 6% Cabernet Franc). The Pavillon blend was pulled together for our tasting and the Le Crock will ultimately have approximately 5% of press wine added to it (we tasted the non-mevushal version, while the US will get the mevushal version). As good as 2015 was (I recommended both the Léoville and Moulin), the 2016 vintage is showing even better all around, with intense fruit and searing tannins in great balance, foreshadowing mind-bending complexity and depth (given the length of the newsletter, full blown notes of the finished wines I tasted will be in a separate missive). Unfortunately pricing will likely be commensurate, so start saving up now.

tastings. An entire wall of the tasting room is covered with the signatures of the entire whose who of the wine world, including Robert Parker, Jancis Robinson and Hugh Johnson. In addition to the star-studded team, the Château also utilizes the services of famed flying winemaker Michel Rolland who, together with the winemaking team and Menachem (for the kosher version) compile the blend. We tasted barrel samples of the 2016 Pavillon (a blend of 67% Cabernet Sauvignon and 33% Merlot (at 60+ years-old, all the Petit Verdot is designated for the higher wines)) and 2016 Le Crock (64% Cabernet Sauvignon, 30% Merlot and 6% Cabernet Franc). The Pavillon blend was pulled together for our tasting and the Le Crock will ultimately have approximately 5% of press wine added to it (we tasted the non-mevushal version, while the US will get the mevushal version). As good as 2015 was (I recommended both the Léoville and Moulin), the 2016 vintage is showing even better all around, with intense fruit and searing tannins in great balance, foreshadowing mind-bending complexity and depth (given the length of the newsletter, full blown notes of the finished wines I tasted will be in a separate missive). Unfortunately pricing will likely be commensurate, so start saving up now.

II. Château Clark

Our next stop was Château Clark, purchased in 1970 by Edmond Rothschild and today owned by his son Benjamin Rothschild, who remains the only branch of the storied Rothschild family to produce kosher wine (although I hope someone will convince Eric (or Saskia) Rothschild to make a kosher run of Lafite sooner or later). Edmond’s grandfather – Baron Rothschild – actually poured more money into Israel’s winemaking industry than he spent acquiring Château Lafite-Rothschild (and look where that got him).

Our next stop was Château Clark, purchased in 1970 by Edmond Rothschild and today owned by his son Benjamin Rothschild, who remains the only branch of the storied Rothschild family to produce kosher wine (although I hope someone will convince Eric (or Saskia) Rothschild to make a kosher run of Lafite sooner or later). Edmond’s grandfather – Baron Rothschild – actually poured more money into Israel’s winemaking industry than he spent acquiring Château Lafite-Rothschild (and look where that got him).

While Edmond owned shares in the family’s vineyards across the world (including Lafite and Argentina’s Fleches de Los Andes which also produces a kosher run), much of his attention was lavished on his own personal properties, Château Clark (where he is buried) and the neighboring Château Malmaison (which he gave to his wife Nadine). The actual structure of Château Malmaison is separate from the winery and is open to the public, having been owned by Empress Joséphine Bonaparte, who renovated the originally rundown estate to an extravagant degree and kept following her divorce from Napoléon. Despite its prestigious history, the estate had fallen into disrepair by the time the Rothschild family acquired it, and represented quite a challenge for Edmond who poured significant resources into the winery, including extensive renovations and updated equipment. However, the biggest change was in the vineyards, where significant portions of Cabernet Sauvignon were replaced with Merlot, deemed better suited to the terroir by wine consultant Emile Peynaud (who was subsequently replaced by Michel Rolland as consultant to the winery), with Merlot currently representing 70% of the Château’s total plantings. Primarily focusing on red blends, the Château also has a few hectares of white varietals (Sauvignon Blanc, Semillon and Muscadelle) which it uses to produce a well-regarded white Bordeaux blend (which will hopefully be produced as a kosher run in the near future).

Starting with the 1986 vintage, Château Clark has been producing the kosher French wine stalwart – Barons Edmond Benjamin de Rothschild – consecutively for 30 years, skipping only the 2009 vintage. Unlike most kosher French wines, it is a wine produced solely for the kosher market and the label doesn’t exist as a non-kosher wine (contrasted to Château Malmaison and the inaugural Château Clark which are produced as kosher runs). The initiative was started by Pierre Miodownick even before he joined Royal Wines back in 1988. The portfolio also includes wines produced from the neighboring Château Malmaison, Château Parsac (located in nearby Montagne-Saint-Émilion) and Château de Laurets (with plots in Montagne-Saint-Émilion and neighboring Puisseguin-Saint-Émilion). In addition to wines sold under the Château’s labels, the Herzog family created the Les Lauriers label and utilizes grapes from Château Parsac to the Les Lauriers rosé and from Château de Laurets to make the Les Lauriers red blend.

Starting with the 1986 vintage, Château Clark has been producing the kosher French wine stalwart – Barons Edmond Benjamin de Rothschild – consecutively for 30 years, skipping only the 2009 vintage. Unlike most kosher French wines, it is a wine produced solely for the kosher market and the label doesn’t exist as a non-kosher wine (contrasted to Château Malmaison and the inaugural Château Clark which are produced as kosher runs). The initiative was started by Pierre Miodownick even before he joined Royal Wines back in 1988. The portfolio also includes wines produced from the neighboring Château Malmaison, Château Parsac (located in nearby Montagne-Saint-Émilion) and Château de Laurets (with plots in Montagne-Saint-Émilion and neighboring Puisseguin-Saint-Émilion). In addition to wines sold under the Château’s labels, the Herzog family created the Les Lauriers label and utilizes grapes from Château Parsac to the Les Lauriers rosé and from Château de Laurets to make the Les Lauriers red blend.

In 2016 Château Clark replaced Michel Rolland with Eric Boissenot as consultant (while the Les Lauriers wines continue to use Michel Rolland’s expert advice) and added Fabrice Darmaillacq as head winemaker (often referred to as technical director in French wineries) who had previously worked at a well-known Landouc winery. Taking advantage of expertise accumulated at his last posting, Fabrice implemented a number of changes intended to upgrade the wine’s quality. Among these changes were incorporating more press wine into the blend to add heft (which is aged separately from the other components), making multiple changes to the chateau’s oak regime and implementing a new pour-over technique. Utilizing the same type of conical vats used by Léoville, he drains the vats causing the hard cap to fall to the bottom of the vat and break into pieces. Then the wine is pumped over the cap which helps control the extraction and achieve a more seductive and complex wine (a process referred to as delestage).

Menachem, Fabrice and I tasted through a plethora of new wines including the first ever vintage (2016) of the winery’s flagship Château Clark and a seven-vintage vertical of the aforementioned Baron Rothschild (1998, 1999 (both non-mevushal), 2007, 2012, 2014, 2015 and barrel-tasted the 2016 (all mevushal)). The 1999 was really nice and at peak now with classic tertiary notes of mushroom and barnyard

Menachem, Fabrice and I tasted through a plethora of new wines including the first ever vintage (2016) of the winery’s flagship Château Clark and a seven-vintage vertical of the aforementioned Baron Rothschild (1998, 1999 (both non-mevushal), 2007, 2012, 2014, 2015 and barrel-tasted the 2016 (all mevushal)). The 1999 was really nice and at peak now with classic tertiary notes of mushroom and barnyard  sharing center stage with subtle black fruit and hints of chocolate while the newer vintages showcased power and balance with green notes and warm spices dominating while the rich fruit needs some time to emerge and the 2016 showing great promise. Other wines tasted included the 2016 Malmaison and the 2015 and 2016 Château Parsac (also from Montagne-Saint-Émilion). We also tasted some Les Lauriers red wines (2010 mevushal and a fun comparative tasting of the mevushal and non-mevushal 2016. The 2016 Clark is 70% Merlot and 30% Cabernet Sauvignon which spent 14 months in new French oak. A deep and powerful wine with layers of complex flavors including rich black fruit, smoke, earthy minerals and chocolate backed by searing tannins and great balance with the fruit, oak and acidity which bodes well for its future. A high quality wine that I look forward to tasting again on release.

sharing center stage with subtle black fruit and hints of chocolate while the newer vintages showcased power and balance with green notes and warm spices dominating while the rich fruit needs some time to emerge and the 2016 showing great promise. Other wines tasted included the 2016 Malmaison and the 2015 and 2016 Château Parsac (also from Montagne-Saint-Émilion). We also tasted some Les Lauriers red wines (2010 mevushal and a fun comparative tasting of the mevushal and non-mevushal 2016. The 2016 Clark is 70% Merlot and 30% Cabernet Sauvignon which spent 14 months in new French oak. A deep and powerful wine with layers of complex flavors including rich black fruit, smoke, earthy minerals and chocolate backed by searing tannins and great balance with the fruit, oak and acidity which bodes well for its future. A high quality wine that I look forward to tasting again on release.

Thank you again to Fabrice for his time and hospitality – it was great learning about the estate and hearing of his plans for the future. I’m also hoping that they make the white wine kosher soon!

III. Château Tertre

With a history dating back to 1143, Château Tertre is one of the oldest château in Bordeaux and is located in the acclaimed Marguax appellation. Benefiting from being owned for a period time during the 1700s by the famous Bordeaux glass blower Pierre Mitchell (who invented the large-format Jeroboam), it was one of the first château to bottle its wine in glass (glass still plays a prominent part in the Château’s story with a roomful of ancient glass wine bottles providing a lovely decorative touch). After centuries of acclaim

With a history dating back to 1143, Château Tertre is one of the oldest château in Bordeaux and is located in the acclaimed Marguax appellation. Benefiting from being owned for a period time during the 1700s by the famous Bordeaux glass blower Pierre Mitchell (who invented the large-format Jeroboam), it was one of the first château to bottle its wine in glass (glass still plays a prominent part in the Château’s story with a roomful of ancient glass wine bottles providing a lovely decorative touch). After centuries of acclaim  the winery’s fortunes declined until it was acquired by Philippe Gasqueton in 1961 who replanted the vineyards, modernized operations and renovated the property. The winery was subsequently sold to the owners of neighboring third-growth Château Giscours (the Jelgersma family) who are the current owners (and represent the path Royal followed to make a kosher cuvee at the winery).

the winery’s fortunes declined until it was acquired by Philippe Gasqueton in 1961 who replanted the vineyards, modernized operations and renovated the property. The winery was subsequently sold to the owners of neighboring third-growth Château Giscours (the Jelgersma family) who are the current owners (and represent the path Royal followed to make a kosher cuvee at the winery).

The estate enjoys one of Margaux’s highest elevations, which is also the source of its name (tertre means hill in French). Comprised of a single block of land, the vineyard is planted with 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 20% Merlot, 15% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot, with the vines averaging 40 years of age and some Cabernet Franc vines over 70 years of age. The estate remains the same size it was when classified as a fifth growth in the 1855 Classification, a rarity for Bordeaux. In addition to the vineyards, the grounds are filled with lovely sculpture-filled gardens, trees and one of the coolest swimming pools ever (where the family makes the most of the summer months it spends in the renovated château, which dates back to the 17th century). With a goal of being 100% Biodynamic farming (the estate is currently 55% biodynamic-farmed), two hectares of vines are replanted every year and replaced with biodynamically farmed

The estate enjoys one of Margaux’s highest elevations, which is also the source of its name (tertre means hill in French). Comprised of a single block of land, the vineyard is planted with 55% Cabernet Sauvignon, 20% Merlot, 15% Cabernet Franc and 5% Petit Verdot, with the vines averaging 40 years of age and some Cabernet Franc vines over 70 years of age. The estate remains the same size it was when classified as a fifth growth in the 1855 Classification, a rarity for Bordeaux. In addition to the vineyards, the grounds are filled with lovely sculpture-filled gardens, trees and one of the coolest swimming pools ever (where the family makes the most of the summer months it spends in the renovated château, which dates back to the 17th century). With a goal of being 100% Biodynamic farming (the estate is currently 55% biodynamic-farmed), two hectares of vines are replanted every year and replaced with biodynamically farmed  vines (the oldest parcel currently dates back to 1962). Tailoring each parcel’s winemaking process includes utilizing a plethora of vinification equipment including wood and stainless steel tanks, concrete eggs and cement vats, each in a number of different sizes with fermentation typically done in 40% oak and 60% cement.

vines (the oldest parcel currently dates back to 1962). Tailoring each parcel’s winemaking process includes utilizing a plethora of vinification equipment including wood and stainless steel tanks, concrete eggs and cement vats, each in a number of different sizes with fermentation typically done in 40% oak and 60% cement.

Together with winemaker (a/k/a technical director) Frédéric Ardouin (who has 10 vintages at Château Tertre under his belt), Menachem and I barrel-tasted the winery’s first kosher release of their flagship wine – Château du Tertre. The blend of 45% Cabernet Sauvignon, 44% Merlot and 11% Cabernet Franc represented the final blend which had spent 14 months in 30% new French oak and then one month in 100% one-year barrels, but Menachem and Frédéric were still debating whether the wine needed additional time in oak. I look forward to tasting the final released version of the elegant and delicious wine.

IV. Château Malartic-Lagravière

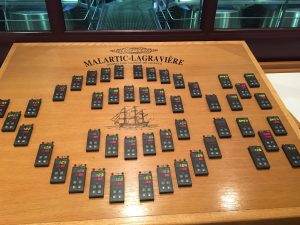

Our last stop of the day was at another estate with roots dating back to the 17th century – Château Malartic-Lagravière. While not included in the 1855 Classification, it was included in the 1953 classification of Graves and is one of only six Bordeaux properties classified for both its red and white wines (other known Graves-Classified kosher wineries are Smith-Haut-Lafite and Pape Clement). Originally known as Domaine de Lagraviere, it was renamed in the 1850’s by its new owners to honor the prior owner-family’s famous son – Comte Anne-Joseph-Hippolyte Maures de Malartic. A well-known colonial Governor and Admiral in the French Navy, it is the Admiral’s nautical connection which accounts for the Navy schooner on the Château’s logo (a large-scale gorgeous model of which is prominently displayed at the chateau. The Château passed through the Ricard (Chevalier) family and was owned for a few years by Laurent Perrier before it was acquired by its current owners – the Bonnie family – in 1997.

Our last stop of the day was at another estate with roots dating back to the 17th century – Château Malartic-Lagravière. While not included in the 1855 Classification, it was included in the 1953 classification of Graves and is one of only six Bordeaux properties classified for both its red and white wines (other known Graves-Classified kosher wineries are Smith-Haut-Lafite and Pape Clement). Originally known as Domaine de Lagraviere, it was renamed in the 1850’s by its new owners to honor the prior owner-family’s famous son – Comte Anne-Joseph-Hippolyte Maures de Malartic. A well-known colonial Governor and Admiral in the French Navy, it is the Admiral’s nautical connection which accounts for the Navy schooner on the Château’s logo (a large-scale gorgeous model of which is prominently displayed at the chateau. The Château passed through the Ricard (Chevalier) family and was owned for a few years by Laurent Perrier before it was acquired by its current owners – the Bonnie family – in 1997.

After earning a fortune in the detergent business, the Bonnie’s directed their attention (and considerable resources) to their new acquisition, pouring close to $20 million into upgrading the estate by replanting many of the vineyards and completely modernizing the property. The capital improvements also including acquiring many new quality vineyards, thus growing the property from the initial 17 hectares to 52 hectares today, with 7 hectares producing white wine (allocated 80% to Sauvignon Blanc and 20% to Semillon, some of which are over 60 years old) and the remaining allocated to their red blends (allocated 45% to Cabernet Sauvignon, 45% to Merlot, 7% to Cabernet Franc and 3% to Petit Verdot) with vines averaging 35 years of age and the best quality vines are Cabernet Sauvignon dating back to 1950 which are those located right outside the winery’s gorgeous tasting room – overlooking the barrel and fermentation areas.

After earning a fortune in the detergent business, the Bonnie’s directed their attention (and considerable resources) to their new acquisition, pouring close to $20 million into upgrading the estate by replanting many of the vineyards and completely modernizing the property. The capital improvements also including acquiring many new quality vineyards, thus growing the property from the initial 17 hectares to 52 hectares today, with 7 hectares producing white wine (allocated 80% to Sauvignon Blanc and 20% to Semillon, some of which are over 60 years old) and the remaining allocated to their red blends (allocated 45% to Cabernet Sauvignon, 45% to Merlot, 7% to Cabernet Franc and 3% to Petit Verdot) with vines averaging 35 years of age and the best quality vines are Cabernet Sauvignon dating back to 1950 which are those located right outside the winery’s gorgeous tasting room – overlooking the barrel and fermentation areas.

Haven been bitten hard by the Bordeaux-bug, the Bonnies acquired an additional Bordeaux property in 2006 – Château Gazin-Rocquencourt located in Pessac Leognan (from which the first kosher run was made for 2015 vintage). Following the model established at Malartic, the Bonnie’s invested significant capital in upgrading Gazin as well, including planting (in 2010) 2 of the property’s 22 hectares for purposes of making a white wine (with the rest allocated 55% to Cabernet Sauvignon and 45% to Merlot). At the same time they further expanded their vinous portfolio and acquired Bodega DiamAndes in Argentina’s famed Mendoza region.

Like many other French wineries, Malartic produces two labels – a Grand Vin – Château Malartic-Lagravière (in both red and white, reflecting their classification for both) and a second wine – La Reserve de Malartic (also a red and white blend). Kosher runs of the red Château Malartic-Lagravière made for the 2003, 2004 and 2005 vintages and then again in 2014 and 2016.

While these days Malartic’s technology may seem standard, when it was installed back in the late 90s it was considered quite revolutionary and stood out as being among the region’s most technologically advanced properties (and today continues to showcase meticulous professionalism and attention to detail). They were among the first using only

While these days Malartic’s technology may seem standard, when it was installed back in the late 90s it was considered quite revolutionary and stood out as being among the region’s most technologically advanced properties (and today continues to showcase meticulous professionalism and attention to detail). They were among the first using only  gravitational pull to move the wine from the fermentation tanks to the oak barrels in the cellar. The red wines are tank fermented, while the white wines are barrel-fermented. Instead of crushing the grapes and pumping the liquid into the fermentation vats they use pulley lifts to bring whole clusters up and into the tanks, which are located above the barrel room. Following whole-cluster fermentation, the wine is dropped into the presses and then flows directly down into the waiting barrels below, all of which helps create a less noticeably tannic and more elegant wine. They also started using a large number of different-sized fermentation containers in their aesthetically-pleasing octagonal-shaped winery, including conical vats, similar to those used by Léoville-Poyferré. Also like Léoville, they use over 30 different vats, each tailored to a different parcel within the vineyard to coax the very best possible result from each one. Other

gravitational pull to move the wine from the fermentation tanks to the oak barrels in the cellar. The red wines are tank fermented, while the white wines are barrel-fermented. Instead of crushing the grapes and pumping the liquid into the fermentation vats they use pulley lifts to bring whole clusters up and into the tanks, which are located above the barrel room. Following whole-cluster fermentation, the wine is dropped into the presses and then flows directly down into the waiting barrels below, all of which helps create a less noticeably tannic and more elegant wine. They also started using a large number of different-sized fermentation containers in their aesthetically-pleasing octagonal-shaped winery, including conical vats, similar to those used by Léoville-Poyferré. Also like Léoville, they use over 30 different vats, each tailored to a different parcel within the vineyard to coax the very best possible result from each one. Other  improvements including implementing a much stricter vineyard selection regime (including harvesting two or three times to ensure perfect ripening for each parcel), which led to allocating a much higher percentage of their fruit to their second wine, helping to greatly improve the quality of their Grand Vin (45% of the red grapes go to the Grand Vine and 55% to the second wine; while 80% of the white goes to the Grand Vin).

improvements including implementing a much stricter vineyard selection regime (including harvesting two or three times to ensure perfect ripening for each parcel), which led to allocating a much higher percentage of their fruit to their second wine, helping to greatly improve the quality of their Grand Vin (45% of the red grapes go to the Grand Vine and 55% to the second wine; while 80% of the white goes to the Grand Vin).

Generally speaking, the red wines spend two years in oak, utilizing 70% new oak for the Grand Vin and 20% new oak for the second wine, while the white wine spends one year in oak, 50% new for the Grand Vine and 20% new for the second wine.

Menachem and I met with Bruno Laplane, who is married to one of the Bonnie’s two daughters Véronique and, together with their son Jean-Jacques and daughter in-law Séverine, manages the estate (with Michel Rolland consulting). Bruno was a  great host, showing us around the winery before we settled into the lovely tasting room to taste the [then-]recently bottled 2015 Château Gazin-Rocquencourt and a barrel sample of the now already bottled and soon to be released 2016 Château Malartic-Lagravière (I also spent some time trying to convince him to make the a kosher run of the white Malartic with Royal as you can see from my energetic hand gesticulations). The Gazin is a rich and elegant wine, showing classic Bordeaux notes of black fruit, herbal nuance with loamy earth and mushroom nose with great tannic backbone and a lingering finish. The 2016 Malartic was also showing great elegance and a more feminine sensuous structure than the Gazin with richer fruit and more elegant expression. Both are lovely.

great host, showing us around the winery before we settled into the lovely tasting room to taste the [then-]recently bottled 2015 Château Gazin-Rocquencourt and a barrel sample of the now already bottled and soon to be released 2016 Château Malartic-Lagravière (I also spent some time trying to convince him to make the a kosher run of the white Malartic with Royal as you can see from my energetic hand gesticulations). The Gazin is a rich and elegant wine, showing classic Bordeaux notes of black fruit, herbal nuance with loamy earth and mushroom nose with great tannic backbone and a lingering finish. The 2016 Malartic was also showing great elegance and a more feminine sensuous structure than the Gazin with richer fruit and more elegant expression. Both are lovely.

V. Drappier

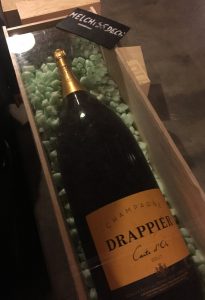

The next day was allocated to a relative newcomer and rising star within the kosher French wine world – the Champagne House of Drappier.

The next day was allocated to a relative newcomer and rising star within the kosher French wine world – the Champagne House of Drappier.

An approximate 2 ½ hour drive from Paris in the Côte des Bar appellation in the Aube region of Champagne, Drappier is a true family Champagne house that was founded in 1808 and is still owned and operated by the family members. Hugo Drappier (8th generation) is the current head of estate (i.e. CEO/COO) while his father Michel Drappier (7th generation) is head winemaker. Michel’s father André (6th generation) is still lending his expertise at 91 and Michel’s other two children Antoine and Charlene are also active with Antoine head of viticulture and in charge of the vineyards while Charlene heads PR and marketing (she also designed the labels).

Drappier was founded in 1803 when patriarch François Drappier moved to Urville and begin working the initial family vineyard which today spans nearly 60 hectares. A then-controversial decision by Michel’s grandfather in the early 1930s to plant Pinot Noir was initially the subject of gentle derision among the other growers and led him to be nicknamed “Father Pinot” but obviously turned out to be the right call as today Pinot Noir is an essential contributor to many of the world’s greatest Champagnes and represents approximately 70% of all grapes grown in the region. Talk about “he who laughs last…” In 1952 added the Carte D’Or to the portfolio and, following massive devastation of the vineyards in 1957 due to heavy frost, Pinot Meunier was planted (a varietal more resistant to icy weather). In 1968 the house continued to innovate with the introduction of a 100% Pinot Noir rosé champagne. Michel has been at the helm since 1973 and continues the family tradition of exploring new varietals (recent plantings have included forgotten grape varieties like Arbane, Petit Meslier and Blanc Vrai). The family also acquired new vineyards of Pinot Noir last year to compensate for the devastating frost of the 2016 and 2017 vintages where significant portion of certain vineyards were lost.

The property is a great combination of new and old with parts of the vaulted cellar dating back to the 12th century and the tasting room lined with wooden panels dated even further back and found on the property. A tour through the cellars is really a walk down memory lane with ancient caverns and dusty bottles occupying space with modern winemaking technology and soon-to-be released bottes of the delicious Champagne. The ancient structure was by Monks (including St. Bernard de Clairvaux) who arrived from Côte de Nuits where they were tending the vines of acclaimed Burgundy property – Clos Vougeot (to date, the only vineyard to produce a Grand Cru kosher run). Among the vines they brought with them and planted in the area where the ancestors of the Pinot Noir grapes comprising a significant portion of Drappier’s current Champagne production. They own 60 hectares and lease

The property is a great combination of new and old with parts of the vaulted cellar dating back to the 12th century and the tasting room lined with wooden panels dated even further back and found on the property. A tour through the cellars is really a walk down memory lane with ancient caverns and dusty bottles occupying space with modern winemaking technology and soon-to-be released bottes of the delicious Champagne. The ancient structure was by Monks (including St. Bernard de Clairvaux) who arrived from Côte de Nuits where they were tending the vines of acclaimed Burgundy property – Clos Vougeot (to date, the only vineyard to produce a Grand Cru kosher run). Among the vines they brought with them and planted in the area where the ancestors of the Pinot Noir grapes comprising a significant portion of Drappier’s current Champagne production. They own 60 hectares and lease  another 60 hectares throughout the Côte des Bar, Montagne de Reims and Côte des Blancs regions. They also purchase an additional 50-60 hectares worth of grapes to fill out their production

another 60 hectares throughout the Côte des Bar, Montagne de Reims and Côte des Blancs regions. They also purchase an additional 50-60 hectares worth of grapes to fill out their production

Current production is approximately 1.6 million bottles a year spread across 11 different wines, including four kosher options. The four kosher options are the soon to be released rosé, the newly released non-dosage, the recently-discontinued (in kosher) Carte Blanch and the houses workhouse – the yellow-labeled Carte D’Or. While many of the wines are barrel fermented, the Carte D’Or is fermented solely in stainless steel and a blend of Pinot Noir, Chardonnay and Pinot Meunier. Kosher production is split around 75% for the Carte D’Or, 20% towards the non-dosage and 5% the new rosé.

Many of the wines will sit in oak for a period of time between six months to two years before they are blended into the final blend (at which point they are bottled, topped with dosage and capped to undergo the second fermentation). To achieve the perfect blend, Michel uses a wide range of differently sized oak barrels in addition to the traditional 225 liter French barrique. Among these are 5,000 liter oak barrels sourced from the 17th century oak forest of Tronçais planted to supply Louie the 14th with wood for his ships. Oak from this forest is known for its tighter grain that imparts a more subtle flavor, making it perfectly suited for white wines.

Many of the wines will sit in oak for a period of time between six months to two years before they are blended into the final blend (at which point they are bottled, topped with dosage and capped to undergo the second fermentation). To achieve the perfect blend, Michel uses a wide range of differently sized oak barrels in addition to the traditional 225 liter French barrique. Among these are 5,000 liter oak barrels sourced from the 17th century oak forest of Tronçais planted to supply Louie the 14th with wood for his ships. Oak from this forest is known for its tighter grain that imparts a more subtle flavor, making it perfectly suited for white wines.

Different from many other Champagne houses who create their large format Champagnes by filling them with multiple bottles of finished regular (750 ml) sized bottles, Drappier’s large format bottles actually undergo their second fermentation in the large format bottles, a process that requires additional cost and effort but which Michel feels imparts a unique profile to the prized larger bottles. Drappier also allows the wine to continue sitting on the lees long after the second fermentation has been completed and only disgorges the wine when the house is ready to release it. This extended process allows many of the cuvees to obtain a richer and more expressive profile that Michel believes is unique to his house (some of the older wines have been sitting on the lees since 1959). Only new oak is used and, keeping with tradition, Drappier still riddles approximately 1/3 of its entire production by hand, including 100% of their large format bottles and all the premium cuvees.